As Election Day looms ever closer, we are starting to see the first party manifestos trickle in. First off the block was the Green party with its most ambitiously – and divisively – environmentally focused manifesto yet.

Scrapping university tuition fees aside, one of the more interesting points on their agenda is to plant 700 million trees by 2030 – more trees in a shorter space of time than any other major party has ever promised before.

The reasoning behind this is well known by now: trees act as excellent natural stores for carbon dioxide and, if we want to start combatting some of our carbon emissions, planting trees is a simple and cost-effective way to go about doing this.

700 million new plants is a lot of trees. To put that number in perspective, only about 15 million trees have been planted under government-backed initiatives in the last eight years, and if every household in the UK planted two trees each, the number of new trees would come to just under 50 million.

So how will this goal be achieved? One proposed solution is through agroforestry.

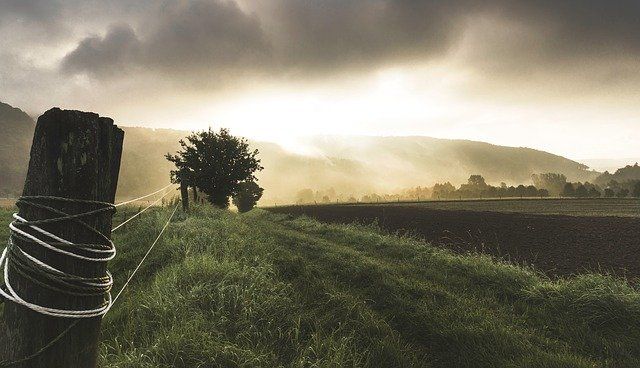

Agroforestry is the practice of farming alongside trees, rather than removing them for the purpose of field sowing or animal rearing as more traditional farming methods would prescribe. So, instead of farming fields being barren and open, they would instead consist of alternating rows of tree-based food crops and more traditional crops grown in the soil below. The same goes for animal farming – animals would co-exist with rows of tree-based crops, rather than living in large, open grazing spaces.

Allowing more trees to grow alongside crops allows for more biodiversity on farms, more shelter for grazing animals, cleaner air, and richer soil resulting from a more complex array of flora.

The system purportedly offers a number of financial benefits, too:

While this all sounds great, actually implementing the system proves difficult.

There would be a huge initial investment required of any farmer willing to make the switch. Soil characteristics aside, not only would their entire farm need to be landscaped and redesigned, but their existing crops and livestock would need to be managed until the process is complete. Further to this, farmers would have to educate themselves about new crops; dairy farmers might have to learn how to successfully grow and harvest chestnuts, and potato farmers might need to learn the intricacies of apple farming. The way farmers and the public think about farming would need to change drastically, and this is certainly no small ask.

Agroforestry presents an interesting dilemma for many farmers, especially in the face of an increased public awareness of climate change and sustainability. Do they adopt, risk a huge initial investment, and potentially reap the social and economic rewards the new system may bring? Or, do they opt for the more conservative approach and look to lower-risk, higher-gain strategies.

The Greens want 50% of farms to be doing agro-forestry in a decade – that’s growing vegetables or raising livestock between rows of trees. This would change the way the countryside looks, but the farmers’ union say it’s not impossible.